The fact that Wegener didn’t really have a convincing mechanism for how continental drift might occur didn’t help his theory gain broad acceptance. “Wegener’s hypothesis… is of the footloose type,” he observed, “in that it takes considerable liberty with our globe, and is less bound by restrictions or tied down by ugly, awkward facts than most of its rival theories.”. Among his detractors was geologist Franz Kossmat, who argued that the oceanic crust was just too tough for continents to “simply plough through.” The University of Chicago’s Rollin T. The American Association of Petroleum Geologists hated the American translation so much it organized a special symposium to oppose the theory of continental drift. Wegener’s hypothesis invited plenty of skepticism, especially from geologists, who resented this outsider’s revolutionary ideas. The last edition was published just before his death in 1930, with the new observation that geologically younger oceans were shallower than their older counterparts. He continued to go on expeditions to gather additional evidence, updating his treatise accordingly. By 1915, he had compiled evidence gleaned from multiple scientific disciplines in support of his theory (dubbed Urkontinent for “All-Lands”) in The Origin of Continents and Oceans. Wegener managed to uncover even more examples of similar organisms on widely separated continents over the next few years.

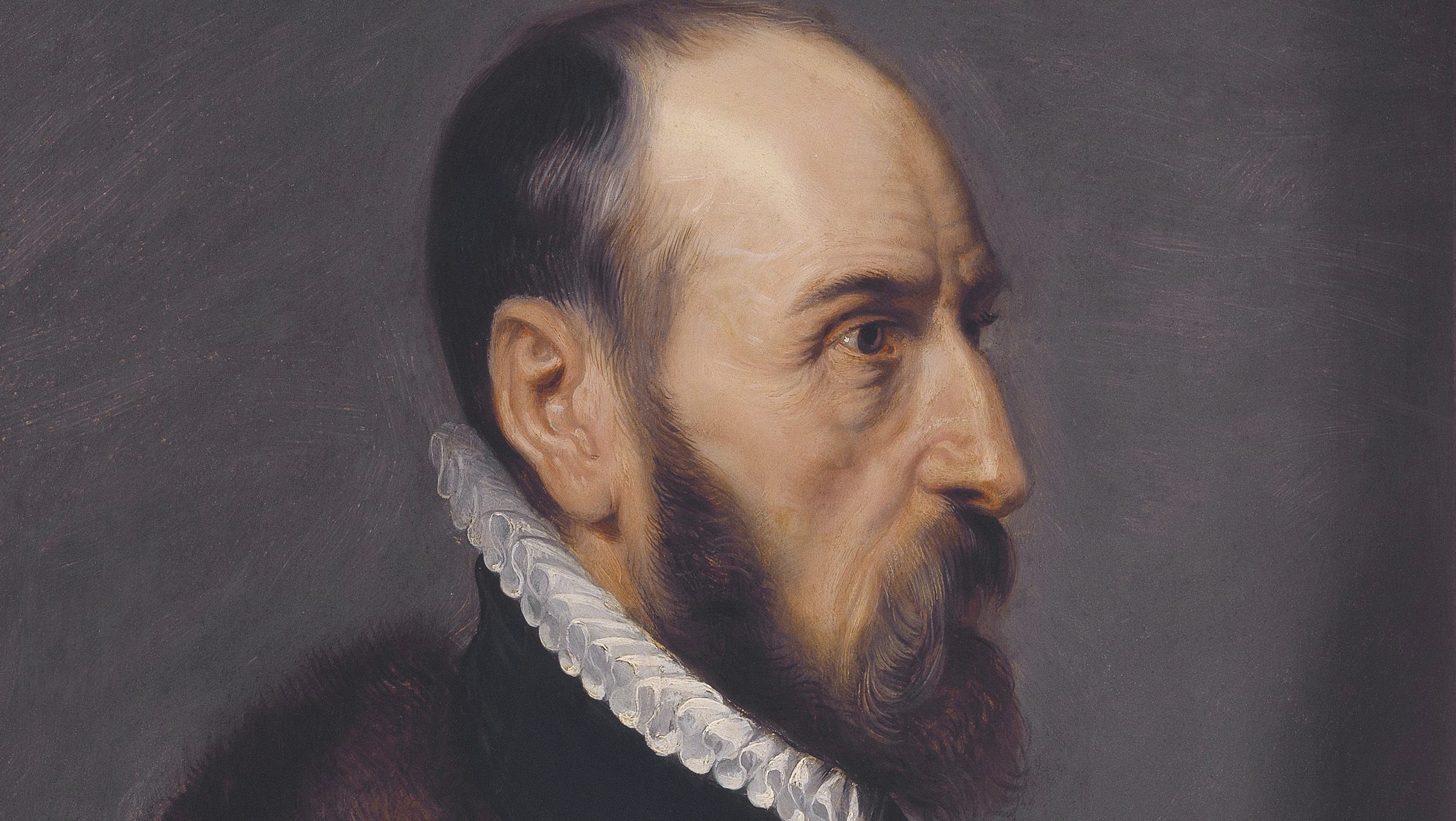

Wegener also originally thought mid-ocean ridges might play some role, since the Atlantic seafloor “is continuously tearing open and making space for fresh, relatively fluid and hot from depth.” But he eventually abandoned those notions. He suggested that the continents were once a single landmass and gradually drifted apart, either because of the centrifugal force of the Earth’s rotation, or some kind of astronomical precession. This contradicted the prevailing hypothesis among geologists at the time, which postulated that land bridges had once connected the continents and were now buried under the ocean. On January 6, 1912, he made the first presentation of his hypothesis of continental drift at a meeting of the German Geological Society in Frankfurt, right before embarking on another scientific expedition to Denmark and Greenland. “A conviction of the fundamental soundness of the idea took root in my mind,” he later wrote. Wegener noticed, as Ortelius did, the same jigsaw puzzle-like shapes of the continents, and how well they seemed to fit together. He noted the striking similarities between types of rock and fossils, especially fossilized plants. While browsing in the university library one day, Wegener happened upon a scientific paper listing fossils of plants and animals on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. He became a tutor at the University of Marburg, taking time out to join expeditions to Greenland in 19 to study polar air circulation. His work in meteorology was especially significant, since he pioneered the use of balloons to track air circulation and published a widely used standard textbook. in astronomy from the University of Berlin in 1904, but his scientific interests were much broader, encompassing geophysics, meteorology, and climatology. But it was a German scientist named Alfred Wegener who developed a robust hypothesis of continental drift over 300 years later.īorn in 1880, Wegener earned his Ph.D. He noted how the geometry of the coasts of America and Europe/Africa seemed to match like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle, and proposed they had gradually drifted apart over time due to earthquakes and floods. Ortelius created the first modern atlas: the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum ( Theater of the World). The notion that the continents were once joined together dates back to at least the 16th century, with the Flemish cartographer and geographer Abraham Ortelius.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)